Updated November 25, 2022

Overview

Many African Americans with the surname Gilliam have their roots in Virginia.

In 1870 there were approximately 340 African Americans enumerated as “Black” with the Gilliam surname. In addition to the 340 enumerated as “Black” approximately another 90 Biracial Gilliams were enumerated as “Mulatto,” for a total of 430. By 1880 the number of “Black” Gilliams was approximately 445, and approximately 110 Biracial Gilliams were enumerated as “Mulatto” for a total of 555.

Some of these African Americans were given the surname Gilliam; others took the name upon themselves.

Others were Gilliams by birth—children of White Gilliams and their Black slaves. Reuben Meriweather Gilliam had several children with Black Silvie Turnbull. Among them was George Torrence Gilliam. George choses to leave Virginia and pursue a medical degree from Dartmouth. He eventually settles in western Pennsylvania and later Illinois. In the 1850 census no race is indicated for George and his family. In the 1860 Census he is enumerated as “Indian” in the 1870 and 1880 Censuses he is enumerated as “White.” The Missouri Death Register lists him as “White.” (The story of George Torrence Gilliam is well-documented in such works as Afro-Virginian History and Culture by John Saillant, Taylor & Francis, 1999; Migrants Against Slavery: Virginians and the Nation by Philip J. Schwarz, 2001 and Making the American Dream Work: A Cultural History of African Americans in Hopewell, Virginia by Lauranett L Lee, Morgan James Publishing, 2008

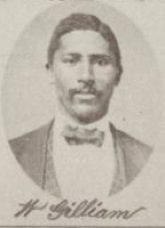

Another descendant of Reuben was William Gilliam who went on to serve as one of the first African Americans in the State Legislature.

Some White Gilliams went to great lengths to explain away the presence of their Biracial relatives. Charles Edgar Gilliam’s Genealogical Data on the Ancestors of Richard Davenport Gilliam, 1855-1935 lists Reuben Meriwether Gilliam as “d. s. p.” “D. s. p.” is an abbreviation for the Latin phrase, descessit sine prole; died without issue. In a correspondence written by Charles Edgar Gilliam dated 23 Mar 1966 Charles states that

“Reuben M. Gilliam was reputed to be a mullato [sic] son of Reuben Meriwether Gilliam. He was not. That Free Man of Color, owner of the old Gilliam Farm Charles was the son of a slave Reuben and a Lady of the Mexican Montezuma Family to whom the three Gilliams who then owned Charles gave the 241 acres and a silver service. His son was the freeman Reuben Montezuma Gilliam that alleged mullato [sic] kinsman was dug up by amateur historians. The father slave was body-servant to Dr. James Skelton Gilliam and accompanied him on a trip to Mexico City.” Charles Edgar Gilliam, later in the same letter states, “Of course, we no doubt have many mullato [sic] kin, but it is not the custom to claim them, though when I was a boy they were talked about inter familias.”

It appears that Silvie Turnbull was reimaged into a lady of Mexican ruler Moctezuma’s family. The rewriting of history was so thorough that there are now among the descendants of Reuben Meriwether Gilliam several individuals named Reuben Moctezuma Gilliam.

The descendants of Basil Human of Humansville, MO reimaged Winnifred George, the widow of Thomas Gilliam into a “Cherokee” in order to explain the dark complexions of Basil’s grandsons. It was Basil, not Winnifred that had African American roots. Basil Human, Sr., is listed in the 1790 Wilkes County, GA tax lists as “mulatto.” It is ironic that Winnifred would “become” Cherokee in light of the fact that her first husband and son were killed by Native Americans and that some of the Human descendants with dark complexions were not Winnifred’s descendants, but rather those of Basil and Jemima Galloway. (Basil leaves Winnifred and lives with and has several children with Winnifred’s daughter-in-law, Jemima.)

Others such as Walter Boyd Gilliam embraced his Black wife Esther Tinsley and their children. His Will provides for Esther and their children. Charles Edgar Gilliam in the above correspondence states the following about Walter Boyd Gilliam: “You are likely to uncover an alleged illegitimate line: Walter Boyd Gilliam, of Petersburg, and his woman.” However, Charles later states in the same correspondence that about “ten years ago” he had seen the original marriage license of Walter Boyd Gilliam and Esther Tinsley.

African American genealogy is difficult at best. The purpose of this page is to begin to gather some of the data regarding African American Gilliams with Virginia roots.

Birth Records

Slave Births

Census

Free Blacks of the 1850 Census

Free Blacks of the 1860 Census

Children's Register

Buckingham County

Prince Edward County

Cohabitation Register

Augusta County

Prince Edward County

Deeds

- Jeremiah Gilliam (Free Negro) to Henry M. Magee, Sussex County, VA

- [Jeremiah was manumitted by the Will of Elizabeth Gilliam, below.]

Willis Gilliam (Free Negro) to Thomas J. Edwards, Sussex County, VA

Freedmen’s Savings

Freedmen’s Savings, 1865-1874

Basil Human and Winnifred George Gilliam, widow of Thomas Gilliam

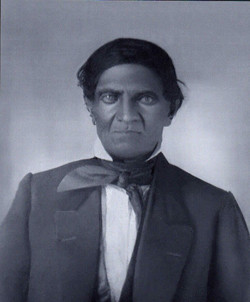

After the death of Thomas Gilliam, Thomas’ widow, Winnifred, married Basil Human. In spite of the best efforts of the descendants of Basil to make Winnifred a Cherokee, the fact cannot be denied that Basil was “mulatto.” His father Basil Human, Sr., is listed in a 1790 Wilkes County, GA tax list as mulatto. Physical descriptions from Civil War records note that Basil’s grandsons have dark complexions and black eyes and hair as one can see from the image of James Gilliam Human, below.

James Gilliam Human

Thomas Jefferson and the Hemings

A President in the Family

Manumissions

22 Sep 1796

Elizabeth Gilliam of Sussex County

My will and desire is that my Negro boy Jeremiah aged about nineteen be bound to a blacksmith trade for four years, and that my Negro girl Patty aged about eighteen be in the service and under the care of David Barrow for five years each from the date hereof at the expiration of which term, I do from an inward conviction of the inequity of hereditary slavery hereby manumit and free them according to the law of this state – gives her interest in slave Jack to her sister Lucy Gilliam–

My will and desire is that all the residue of my estate of what kind or quality soever be sold and after paying just debts and financial expenses the money arising therefrom one half I give and bequeath to my sister Sarah Barrow and the other half I give and bequeath with the interest arising thereon to be equally divided between the above mentioned Negroes Jeremiah and Patty to be by them possessed at the end of their years of service

Rec. 1 Dec. 1796

Sussex County, VA, Will Book F 1796-1806, p. 1 –

21 Aug. 1801

Lucey Gilliam of Parish of Albemarle, County of Sussex

My will is that my man Joel shall advance or cause to be advanced by hire the sum of fifty pounds after that I do manumit or free the said Joel. My will is that my woman Dinah shall be hired so long as to raise the sum of ten pounds after that I do manumit or free the said Dinah. My will is that my woman Edy should be hired out three years after then she the said Edy shall be free, and as the said Edy is pregnant my will is that the child she may bring shall be free. Whereas my man Jack is under incumberance so my sister Edna claims one third part of the said Jack, my will is that the said Negro be hired out so long as to pay my sister one third part of his value and after then the said Jack shall be free and remainder of my estate I leave to be sold

Rec. 5 Nov 1801

Sussex County, VA, Will Book F 1796-1806, p. 263 –

27 Aug. 1801

Levi Gilliam, Sr of Albemarle Parish in Sussex County

My will and desire is that all the rest and residue of my estate of what kind so ever except my Negro man named Robbin which I hereby liberate and set free, but desire him may live with my daughter Lucy Wilborne during his life, may be sold and the money arising from such sale after my just death and funeral expenses are paid I give and bequeath to my two daughters

27 Aug. 1801

Rec. 4 Feb. 1802

Sussex County, VA, Will Book F 1796-1806, p. 282

7 Nov 1814

Will of William Gilliam of Sussex

Has land in Surry and lots in Blandford ie Petersburg–it is my will and desire that my negro Girl Decca be comfortably supported in my Estate for the term of fifteen years from the time of my decease and she, the said Decca, to have ten dollars a year to be paid to her yearly out of my estate by my execs

Rec 1 Dec 1814

Sussex County, VA, Will Book H 1813-1818p.124–

Politicians

1871-1872

Legislature of Virginia, session 1871 and 1872

Wm. Gilliam

[The 1871–1872 session of the Virginia General Assembly included some of the first African Americans to hold public office in the state. In 1870 William Gilliam was living in the household of his father Reuben and his mother, Patience Walker. William is listed as a mulatto. William is the grandson of Reuben Meriwether Gilliam. In 1880 William, age 38, is listed with wife Susan and five children: John H., Martha, Louisa L., William S., and Lucrecia. William is again listed as a farmer. See Negro Office-Holders in Virginia, 1865-1895, by Luther Porter Jackson, Guide Quality Press, 1945.]

Register of Free Negroes

Petersburg

Slave Schedules

1860 Slave Schedule

Southern Claims

Reuben M. Gilliam, the son of Reuben Meriwether Gilliam and Silvie Turnbull, married Patience Walker. After the Civil War, Reuben registered claims for supplies confiscated by the army.

Underground Railroad

According to William Still, William Henry Gilliam, slave of Mrs. Louisa White of Richmond escapes to Canada aboard a steamer. Mrs. White pleads for William to return; he, however, remains in Canada. The following is an excerpt from William Still’s book,

JAMES MERCER, WM. H. GILLIAM, AND JOHN CLAYTON STOWED AWAY IN A HOT BERTH.

This arrival came by Steamer. But they neither came in State-room nor as Cabin, Steerage, or Deck passengers.

A certain space, not far from the boiler, where the heat and coal dust were almost intolerable,—the colored steward on the boat in answer to an appeal from these unhappy bondmen, could point to no other place for concealment but this. Nor was he at all certain that they could endure the intense heat of that place. It admitted of no other posture than lying flat down, wholly shut out from the light, and nearly in the same predicament in regard to the air. Here, however, was a chance of throwing off the yoke, even if it cost them their lives. They considered and resolved to try it at all hazards.

Henry Box Brown's sufferings were nothing, compared to what these men submitted to during the entire journey.

They reached the house of one of the Committee about three o'clock, A.M.

All the way from the wharf the cold rain poured down in torrents and they got completely drenched, but their hearts were swelling with joy and gladness unutterable. From the thick coating of coal dust, and the effect of the rain added thereto, all traces of natural appearance were entirely obliterated, and they looked frightful in the extreme. But they had placed their lives in mortal peril for freedom.

Every step of their critical journey was reviewed and commented on, with matchless natural eloquence,—how, when almost on the eve of suffocating in their warm berths, in order to catch a breath of air, they were compelled to crawl, one at a time, to a small aperture; but scarcely would one poor fellow pass three minutes being thus refreshed, ere the others would insist that he should "go back to his hole." Air was precious, but for the time being they valued their liberty at still greater price.

After they had talked to their hearts' content, and after they had been thoroughly cleansed and changed in apparel, their physical appearance could be easily discerned, which made it less a wonder whence such outbursts of eloquence had emanated. They bore every mark of determined manhood.

The date of this arrival was February 26, 1854, and the following description was then recorded—

Arrived, by Steamer Pennsylvania, James Mercer, William H. Gilliam and John Clayton, from Richmond.

James was owned by the widow, Mrs. T.E. White. He is thirty-two years of age, of dark complexion, well made, good-looking, reads and writes, is very fluent in speech, and remarkably intelligent. From a boy, he had been hired out. The last place he had the honor to fill before escaping, was with Messrs. Williams and Brother, wholesale commission merchants. For his services in this store the widow had been drawing one hundred and twenty-five dollars per annum, clear of all expenses.

He did not complain of bad treatment from his mistress, indeed, he spoke rather favorably of her. But he could not close his eyes to the fact, that at one time Mrs. White had been in possession of thirty head of slaves, although at the time he was counting the cost of escaping, two only remained—himself and William, (save a little boy) and on himself a mortgage for seven hundred and fifty dollars was then resting. He could, therefore, with his remarkably quick intellect, calculate about how long it would be before he reached the auction block.

He had a wife but no child. She was owned by Mr. Henry W. Quarles. So out of that Sodom he felt he would have to escape, even at the cost of leaving his wife behind. Of course he felt hopeful that the way would open by which she could escape at a future time, and so it did, as will appear by and by. His aged mother he had to leave also.

Wm. Henry Gilliam likewise belonged to the Widow White, and he had been hired to Messrs. White and Brother to drive their bread wagon. William was a baker by trade. For his services his mistress had received one hundred and thirty-five dollars per year. He thought his mistress quite as good, if not a little better than most slave-holders. But he had never felt persuaded to believe that she was good enough for him to remain a slave for her support.

Indeed, he had made several unsuccessful attempts before this time to escape from slavery and its horrors. He was fully posted from A to Z, but in his own person he had been smart enough to escape most of the more brutal outrages. He knew how to read and write, and in readiness of speech and general natural ability was far above the average of slaves.

He was twenty-five years of age, well made, of light complexion, and might be put down as a valuable piece of property.

This loss fell with crushing weight upon the kind-hearted mistress, as will be seen in a letter subjoined which she wrote to the unfaithful William, some time after he had fled.

LETTER FROM MRS. L.E. WHITE.

RICHMOND, 16th, 1854.

DEAR HENRY

Your mother and myself received your letter; she is much distressed at your conduct; she is remaining just as you left her, she says, and she will never be reconciled to your conduct.

I think Henry, you have acted most dishonorably; had you have made a confidant of me I would have been better off; and you as you are. I am badly situated, living with Mrs. Palmer, and having to put up with everything—your mother is also dissatisfied—I am miserably poor, do not get a cent of your hire or James', besides losing you both, but if you can reconcile so do. By renting a cheap house, I might have lived, now it seems starvation is before me. Martha and the Doctor are living in Portsmouth, it is not in her power to do much for me. I know you will repent it. I heard six weeks before you went, that you were trying to persuade him off—but we all liked you, and I was unwilling to believe it—however, I leave it in God's hands He will know what to do. Your mother says that I must tell you servant Jones is dead and old Mrs. Galt. Kit is well, but we are very uneasy, losing your and James' hire, I fear poor little fellow, that he will be obliged to go, as I am compelled to live, and it will be your fault. I am quite unwell, but of course, you don't care.

Yours,

L.E. WHITE.

If you choose to come back you could. I would do a very good part by you, Toler and Cooke has none.

This touching epistle was given by the disobedient William to a member of the Vigilant Committee, when on a visit to Canada, in 1855, and it was thought to be of too much value to be lost. It was put away with other valuable U.G.R.R. documents for future reference. Touching the "rascality" of William and James and the unfortunate predicament in which it placed the kind-hearted widow, Mrs. Louisa White, the following editorial clipped from the wide-awake Richmond Despatch, was also highly appreciated, and preserved as conclusive testimony to the successful working of the U.G.R.R. in the Old Dominion. It reads thus—

"RASCALITY SOMEWHERE.—We called attention yesterday to the advertisement of two negroes belonging to Mrs. Louisa White, by Toler & Cook, and in the call we expressed the opinion that they were still lurking about the city, preparatory to going off. Mr. Toler, we find, is of a different opinion. He believes that they have already cleared themselves—have escaped to a Free State, and we think it extremely probable that he is in the right. They were both of them uncommonly intelligent negroes. One of them, the one hired to Mr. White, was a tip-top baker. He had been all about the country, and had been in the habit of supplying the U.S. Pennsylvania with bread; Mr. W. having the contract. In his visits for this purpose, of course, he formed acquaintances with all sorts of sea-faring characters; and there is every reason to believe that he has been assisted to get off in that way, along with the other boy, hired to the Messrs. Williams. That the two acted in concert, can admit of no doubt. The question is now to find out how they got off. They must undoubtedly have had white men in the secret. Have we then a nest of Abolition scoundrels among us? There ought to be a law to put a police officer on board every vessel as soon as she lands at the wharf. There is one, we believe for inspecting vessels before they leave. If there is not there ought to be one.

"These negroes belong to a widow lady and constitute all the property she has on earth. They have both been raised with the greatest indulgence. Had it been otherwise, they would never have had an opportunity to escape, as they have done. Their flight has left her penniless. Either of them would readily have sold for $1200; and Mr. Toler advised their owner to sell them at the commencement of the year, probably anticipating the very thing that has happened. She refused to do so, because she felt too much attachment to them. They have made a fine return, truly."

No comment is necessary on the above editorial except simply to express the hope that the editor and his friends who seemed to be utterly befogged as to how these "uncommonly intelligent negroes" made their escape, will find the problem satisfactorily solved in this book.

However, in order to do even-handed justice to all concerned, it seems but proper that William and James should be heard from, and hence a letter from each is here appended for what they are worth. True they were intended only for private use, but since the "True light" (Freedom) has come, all things may be made manifest.

LETTER FROM WILLIAM HENRY GILLIAM.

ST. CATHARINES, C.W., MAY 15th, 1854.

My Dear Friend:

I receaved yours, Dated the 10th and the papers on the 13th, I also saw the pice that was in Miss Shadd's paper About me. I think Tolar is right About my being in A free State, I am and think A great del of it. Also I have no compassion on the penniless widow lady, I have Served her 25 yers 2 months, I think that is long Enough for me to live A Slave. Dear Sir, I am very sorry to hear of the Accadent that happened to our Friend Mr. Meakins, I have read the letter to all that lives in St. Catharines, that came from old Virginia, and then I Sented to Toronto to Mercer & Clayton to see, and to Farman to read fur themselves. Sir, you must write to me soon and let me know how Meakins gets on with his tryal, and you must pray for him, I have told all here to do the same for him. May God bless and protect him from prison, I have heard A great del of old Richmond and Norfolk. Dear Sir, if you see Mr. or Mrs. Gilbert Give my love to them and tell them to write to me, also give my respect to your Family and A part for yourself, love from the friends to you Soloman Brown, H. Atkins, Was. Johnson, Mrs. Brooks, Mr. Dykes. Mr. Smith is better at presant. And do not forget to write the News of Meakin's tryal. I cannot say any more at this time; but remain yours and A true Friend ontell Death.

W.H. GILLIAM, the widow's Mite.

"Our friend Minkins," in whose behalf William asks the united prayers of his friends, was one of the "scoundrels" who assisted him and his two companions to escape on the steamer. Being suspected of "rascality" in this direction, he was arrested and put in jail, but as no evidence could be found against him he was soon released.

JAMES MERCER'S LETTER.

TORONTO, MARCH 17th, 1854.

My dear friend Still:

I take this method of informing you that I am well, and when this comes to hand it may find you and your family enjoying good health. Sir, my particular for writing is that I wish to hear from you, and to hear all the news from down South. I wish to know if all things are working Right for the Rest of my Brotheran whom in bondage. I will also Say that I am very much please with Toronto, So also the friends that came over with. It is true that we have not been Employed as yet; but we are in hopes of be'en so in a few days. We happen here in good time jest about time the people in this country are going work. I am in good health and good Spirits, and feeles Rejoiced in the Lord for my liberty. I Received cople of paper from you to-day. I wish you see James Morris whom or Abram George the first and second on the Ship Penn., give my respects to them, and ask James if he will call at Henry W. Quarles on May street oppisit the Jews synagogue and call for Marena Mercer, give my love to her ask her of all the times about Richmond, tell her to Send me all the news. Tell Mr. Morris that there will be no danger in going to that place. You will also tell M. to make himself known to her as she may know who sent him. And I wish to get a letter from you.

JAMES M. MERCER.

JOHN H. HILL'S LETTER.

My friend, I would like to hear from you, I have been looking for a letter from you for Several days as the last was very interesting to me, please to write Right away.

Yours most Respectfully,

JOHN H. HILL.

Instead of weeping over the sad situation of his "penniless" mistress and showing any signs of contrition for having wronged the man who held the mortgage of seven hundred and fifty dollars on him, James actually "feels rejoiced in the Lord for his liberty," and is "very much pleased with Toronto;" but is not satisfied yet, he is even concocting a plan by which his wife might be run off from Richmond, which would be the cause of her owner (Henry W. Quarles, Esq.) losing at least one thousand dollars,

ST. CATHARINE, CANADA, JUNE 8th, 1854.

MR. STILL, DEAR FRIEND:

I received a letter from the poor old widow, Mrs. L.E. White, and she says I may come back if I choose and she will do a good part by me. Yes, yes I am choosing the western side of the South for my home. She is smart, but cannot bung my eye, so she shall have to die in the poor house at last, so she says, and Mercer and myself will be the cause of it. That is all right. I am getting even with her now for I was in the poor house for twenty-five years and have just got out. And she said she knew I was coming away six weeks before I started, so you may know my chance was slim. But Mr. John Wright said I came off like a gentleman and he did not blame me for coming for I was a great boy. Yes I here him enough he is all gas. I am in Canada, and they cannot help themselves.

About that subject I will not say anything more. You must write to me as soon as you can and let me here the news and how the Family is and yourself. Let me know how the times is with the U.G.R.R. Co. Is it doing good business? Mr. Dykes sends his respects to you. Give mine to your family.

Your true friend,

W.H. GILLIAM

Still, William. By Themselves and Others, or Witnessed By The Author; Together With Sketches of Some of The Largest Stockholders, And Most Liberal Aiders And Advisers, of The Road.

Wills, Estates and Inventories

Will of Rebecca N. Mathews

Sources